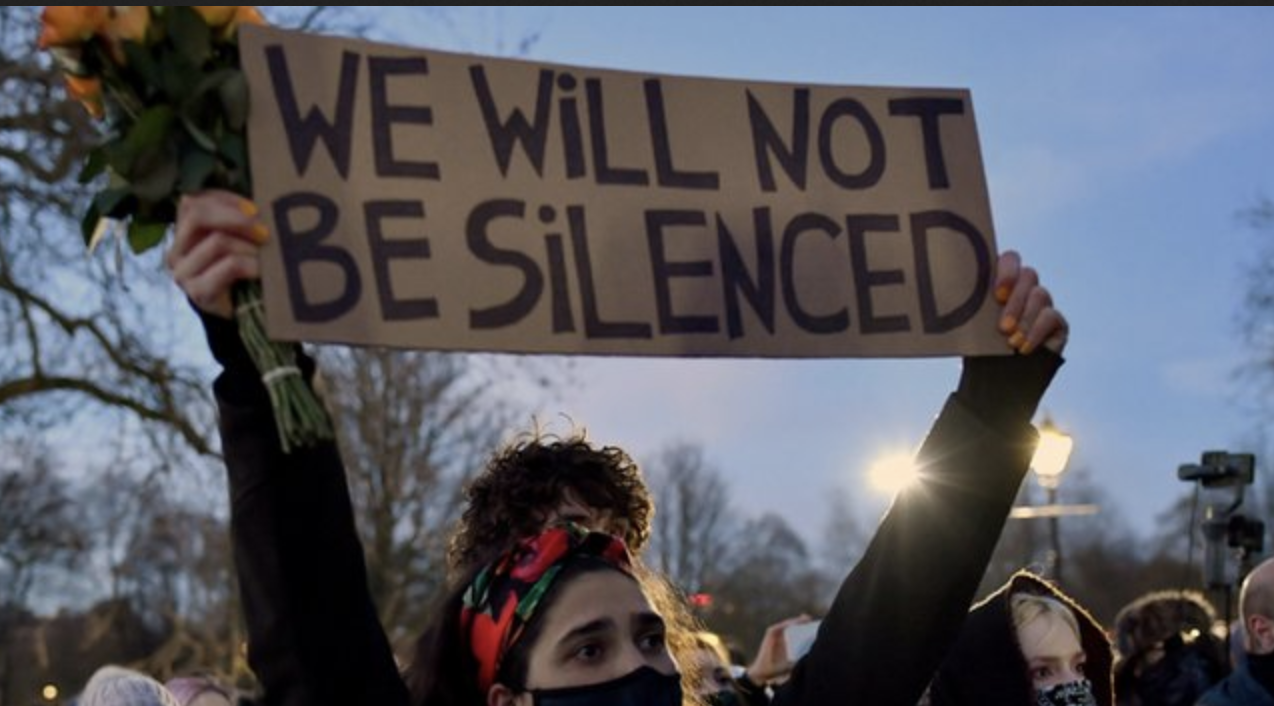

Last week, women across the UK gathered to express collective grief and anger at the kidnap and murder of Sarah Everard, whose body has now been formally identified after she was reported missing three weeks ago. From the large gathering that was forcibly broken up by police in Clapham — the place Sarah was last seen — to smaller tributes and vigils such as the one I attended in Oxford, to individuals lighting candles in their own homes, it seems Sarah Everard’s abduction from the streets of the capital has deeply shaken thousands of women.

Often when women are murdered by men, we can feel anger on behalf of the victim without feeling ourselves to be particularly at risk. We tell ourselves that since we aren’t in abusive relationships, or we aren’t involved in prostitution, we’re safe. As far as the public is aware though, neither of these circumstances applied to Sarah Everard. It wasn’t especially late when she walked home, she wasn’t drunk after a night out, nor was she wearing so-called “provocative” clothing. The neighbourhood she was walking in is a byword for yuppie gentrification and certainly not one that many would consider dangerous. CCTV shows her walking along a main road while talking to her partner on the phone. And yet, she disappeared. Many women find this frightening and disturbing because they wouldn’t think twice about doing exactly what Sarah did.

Other elements of this case also make it particularly disturbing. The fact that the man charged with her murder is a police officer. The fact that police are now carrying out an investigation into whether more minor accusations against the same man weeks prior were dealt with appropriately: the implication being that, perhaps if they had been taken more seriously, Sarah might still be alive; and also that if a man flashes you, he might be a murderer (and the police might not care). Then there is the fact that, before the suspect was arrested, police reportedly warned women to be careful going out alone, which has of course fuelled the usual controversies over women curtailing their behaviour due to the threat of violence from men. And finally, there’s the grim drip-dripping inevitability of it: woman missing; family concerned; searching ponds, but not assuming anything yet — man arrested but not charged; man charged with murder; “human remains;” “dental records” — yes, it’s her. It’s given this unfolding story a sickening “can’t look away, even though we all know how it ends” quality which is all too tragically familiar.

With this kind of nightmare story, it’s virtually always human female remains, and virtually always a man arrested. It seems trite to point out, because we all know it’s true. And yet, despite the obviousness of this statement, each case is seen as an isolated tragedy rather than part of a wider pattern worth remarking on. As one Twitter user commented, “If female on male violence were a thing like this, we’d be in ankle tags at the very best.”

This is not the first time women have been warned to stay at home for their own safety. During the late 1970s when Peter Sutcliffe — the “Yorkshire Ripper” — was attacking and killing women across Northern England, terrified women were told by police: “Do not go out at night unless absolutely necessary and only if accompanied by a man you know,” provoking an upswelling of anger from feminists who demanded a curfew on men, not themselves. (Julie Bindel claims this was what radicalized her as a teenager).

Forty years later, little has changed. Less than a month before the women of Clapham were told the same thing, police in Basildon, Essex warned women not to go out alone after a spate of sexual assaults in broad daylight. In 2020, women were told to stay home in Belfast, after a spree of violence in which a man attacked five female members of the public with a knife; in Lincoln, after a teenager was sexually assaulted; and in Anglesey, following a string of indecent exposures and assaults on women. Of these, only the Belfast incident made national rather than local news, and it was a very minor story that was not reported by most newspapers and was soon forgotten.

Can you imagine how big of a news story it would be — and rightly so — if a UK police branch announced that members of an ethnic or religious minority should stay home or else risk being targeted for sexual assault, abduction, or murder? It would be regarded as an appalling failure of policing, effectively saying: people want to hurt you, and we can’t protect you — you’re on your own. This happens again and again to women in towns and cities all over the UK, and it’s business as usual. It’s almost as though male violence against women is like weather: you have to plan around it, but it’s not personal, it just is.

If someone is harassed, physically attacked, or killed because of their race or sexuality, that is a “hate crime” in UK law. Perpetrators of these crimes can often receive a heavier sentence, and specialized governmental and policing groups work to monitor and reduce hate crime. However, there’s no such thing in UK law as a hate crime motivated by sex. This is despite the vast majority of sexual offences — from street harassment to abduction, rape, and murder — happening almost by definition because the victim is a woman or girl (Donald Trump wasn’t interested in grabbing men by the penis), and despite the fact that often the offender is explicitly motivated by hatred or disdain for women. In other words, as stated in the Metropolitan Police’s definition of hate crime, “It is who the victim is … that motivates the offender.”

Arguably, this omission is because the sheer volume of hate crimes directed at women would overwhelm the system. Arguably, it is because misogyny is so deeply naturalized, with the division between the sexes running through every family back to the dawn of our species, that it is just very hard to see that women are systematically the victims of crimes because of their sex.*

You might be excused for assuming this blind spot for sexism is an outdated status quo that will soon be consigned to history. Unbelievably, however, the idea that women aren’t meaningfully discriminated against for being women is being actively maintained in progressive politics today.

Just last week, the SNP’s controversial Hate Crime Bill was passed, after an amendment to include sex as a protected characteristic was rejected. However, the bill does take care to explicitly include “cross-dressers.” When one compares the vast global scale of violence against women to the number of crimes directed specifically at cross-dressers, the deliberate omission of sex is inexplicable. The same week, the Green Party of England and Wales voted against a motion that would have seen sex recognized by the party alongside the other protected characteristics of the Equality Act. In February, expert women-focused domestic violence services in Brighton and in North Lanarkshire both lost their funding in favour of “non-gendered” services that will devote more attention to heterosexual and gay male victims, despite the fact that an overwhelming majority of victims are women. Nowadays, sexism isn’t just invisible — it’s taboo, or just embarrassingly passé.

The last week on social media has seen an outpouring of women talking about the ubiquity of sexual harassment, and the precautions they feel they have to take because of male violence. Progressive men have largely made the right noises about needing to listen and do better. However, in an environment where sexism is demonstrably not taken seriously in politics and where women are routinely shunned and demonized for raising concerns about male violence, this all feels rather hollow to me.

Many of those taking to Twitter to tell us to #BelieveWomen and #YesAllWomen very quickly forget these principles the moment it counts. If you don’t believe me, try telling your progressive circle of friends that male sex offenders should not be housed in women’s prisons. You could add that women have allegedly been raped as a result of this policy, as any fool could have predicted. Rather than justified feminist outrage, you will likely be met with embarrassed silence at best, or some hemming and hawing about how it’s a “difficult issue;” or, at worst, ostracism and accusations of bigotry. Middle class women are allowed to be afraid to go jogging after dark, but there is no sympathy for incarcerated women — some of the most vulnerable members of society, large numbers of whom have prior trauma at the hands of males — who are now locked up with convicted rapists. Any concern raised is just hateful scaremongering masking a conservative agenda.

If you shared one of the cartoons on Instagram debunking #NotAllMen (it’s not personal, it’s a sensible precaution to be wary of all men given the bad actions of some) then what do you say to women who feel intimidated by the presence of males who identify as female in domestic violence refuges? They should just swallow their discomfort, because… Not Those Men? It’s easy to pay lip service in the form of, “Women: if a man is making you feel uncomfortable, don’t spare his feelings — your safety is more important.” It’s much harder to speak up for female boundaries when it actually does hurt male feelings.

With that in mind, do you support the signs cropping up on university campuses, which explicitly tell women that in certain situations they should ignore their discomfort because it’s impolite not to, and shame them for feeling discomfort in the first place? If someone complained about these signs, would you think she was justified, or would you roll your eyes and call her a “Karen” who is making a fuss over nothing? Would you tell women, just like the police have so many times, that if they aren’t comfortable using “all gender” bathrooms — which data shows are less safe for women — they should just stay home? In summer 2020, when JK Rowling explained that she shared many of these concerns as a result of her experience with male violence, did you nod along when people accused her of paranoia and of “weaponizing” her abuse? Do you think she deserved what she got for speaking up?

Those who only support women’s boundaries when it’s a boundary against members of the out-group, not the in-group, do not really support women’s right to draw boundaries at all. If you only stand with women when it’s socially or politically easy to do so, then you aren’t a feminist, you’re a hypocrite. Until we firmly establish that women always have the right to express their concerns and have them taken seriously, we have no hope of defeating the attitudes that allow male violence against women to thrive.

Ellen Pasternack is a PhD student in evolutionary biology living in Oxford, UK.

*It should be noted that not all feminists are in favour of expanding hate crime legislation to include women. However, I highly doubt feminist objections were the reason for the omission of women when the law was drawn up.