We all agree stalking, violence, and murder are bad things, yet millions enjoy them as a thrilling and sometimes titillating form of entertainment.

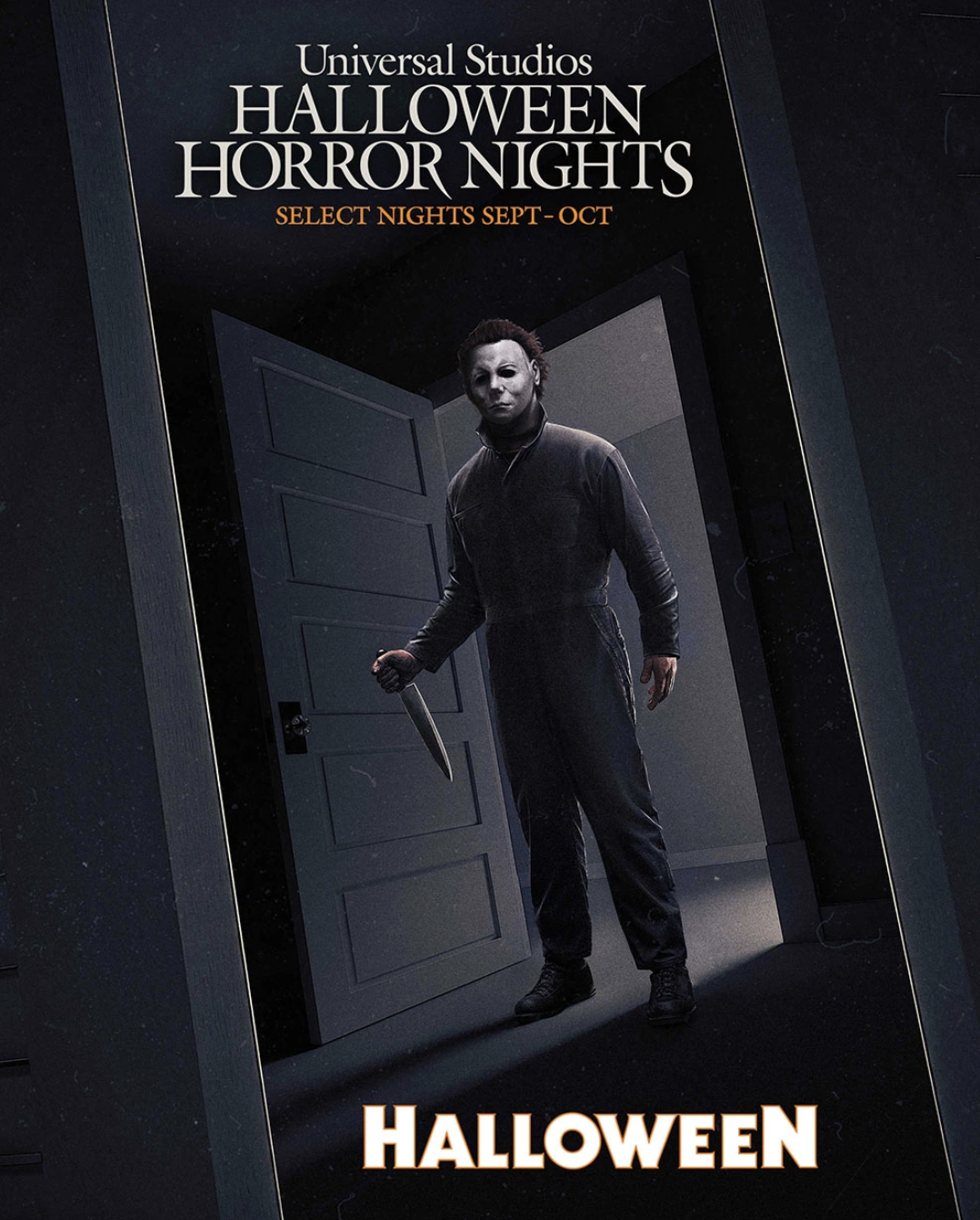

Both Universal Studios’ Hollywood and Orlando theme parks feature a Halloween-themed haunted house this fall as part of their Halloween Horror Nights events. The popular slasher franchise, originated in 1978 with John Carpenter’s Halloween, now includes 13 films. The latest installment, Halloween Ends, was released last week. The films centre on a serial killer named Michael Myers who targets women and girls in particular — hunting, terrorizing, and brutally murdering them.

Given that male violence against women and girls is ubiquitous, filling headlines daily, the choice to turn these stories into entertainment at amusement parks and in Hollywood films is troubling.

This fall, Universal invites us to, “Gather your friends and visit Haddonfield, Illinois, where Michael Myers is about to don his mask and embark on his first brutal spree.” Myers, we are told, is “the embodiment of pure evil… silent, merciless, and relentless.”

The marketing trailer features a woman alone in her home. The power goes out and she is startled by the sudden appearance of a strange, masked man holding a large knife in her hallway. She is frozen in fear but does not scream. When the lights come back on, Michael Myers is gone, and she tells herself what she saw wasn’t real. The video cuts to a poster for Halloween Horror Nights with a note directing attendees to review Universal’s safety guidelines, not to wear costumes or masks to the event, and warning that the haunted house is not recommended for children under 13. We then see two female attendees screaming as an actor playing Myers, brandishing a large knife above his head, attacks them.

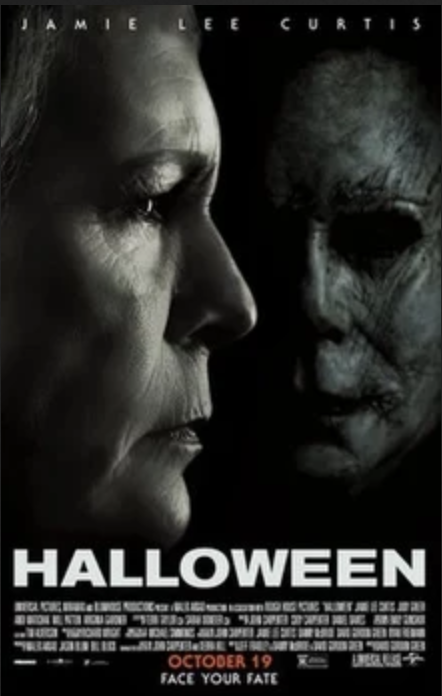

Universal’s Halloween haunted house will allow visitors to “step into the original 1978 horror classic, Halloween.” For those unfamiliar, Halloween is the story of teenaged Laurie Strode (played by Jamie Lee Curtis), and her friends, Annie and Lynda, who are stalked on Halloween night by escaped killer, Michael Myers. As the story goes, Myers brutally murdered his older sister, Judith, 15 years earlier, when he was just six years old. The 1978 film follows Myers as he hunts Laurie one evening while she is babysitting, murdering her friends in his efforts to terrorize her.

Like in many horror films, the female characters are sexualized — violence made titillating.

Judith is shown topless — brushing her hair in just her underwear — as Myers approaches, stabbing her repeatedly. She collapses on the floor, her naked breasts covered in blood. When Myers murders Annie, she is outside in just a shirt, panties, socks, and shoes. We see Lynda and her boyfriend, Bob, in bed, after having had sex. When Bob leaves the room, Myers kills him, before heading upstairs, disguised in a sheet. Myers approaches Lynda in bed, who she mistakes for Bob, and, lowering the sheet to display her breasts, asks him, “See anything you like?” Lynda calls Laurie, and Myers strangles her as Laurie listens on the phone.

The film is a misogynist celebration of terrorization and sexualized violence against adolescent girls — presumably, visitors to Universal’s Halloween haunted house can expect a continuation of this theme.

Halloween is not made for female audiences. The male viewer is positioned as Myers himself in POV shots where young women are spied on, stalked, attacked, and murdered, providing the fantasy of being the voyeur and perpetrator.

Not only are women the targets, but they are disbelieved when they try to warn others. When Laurie tells Annie that the man Annie yelled at when he drove by is now hiding behind the bushes up ahead Annie says, “I think you’re wacko. Now you’re seeing men behind bushes.” The fact that a man who brutally murders two teenage girls continues to get away with his crimes, sends a clear message: females are perpetually vulnerable, their attackers never held to account. More consideration is shown to a dog than to female viewers — the dog Michael Myers kills and eats is mentioned rather than shown.

Even children are made part of the misogynist male fantasy. As Lynda and Bob are making plans to sneak upstairs and have sex while babysitting nine-year-old Lindsey, Bob says, “First I rip your clothes off… Then you rip my clothes off, then we rip Lyndsey’s clothes off.” Lynda laughs and replies, “Totally.”

Carpenter’s 1978 slasher classic made US$70 million at the worldwide box office (in unadjusted dollars). The apparent popularity of this kind of sadism birthed a franchise, which has now, after 11 more Halloween movies, made over US$773 million — a figure that does not reflect novelizations, related young adult novels, comic books, merchandise, or newest film. Universal’s Halloween haunted houses in Hollywood and Orlando are just the latest additions to the lucrative franchise (admission to Halloween Horror Nights starts at US$74+tax).

The latest Halloween trilogy, directed by David Gordon Green — Halloween (2018), Halloween Kills (2021), and Halloween Ends (2022) — sees Michael Myers continue to hunt and terrorize Laurie Strode, as well as her daughter Karen and her granddaughter Allyson.

Halloween (2018) picks up the story 40 years after the 1978 film, ignoring the franchise’s subsequent installments. Two true crime podcasters covering the story of Michael Myers tell Laurie they believe there is “a lot to learn from the horrors [she] experienced.” Laurie tells them, “There’s nothing to learn. There are no new insights or discoveries.” By the filmmakers’ own admission, conveyed through the character of Sam Loomis, Myer’s psychiatrist and caretaker, this man is “nothing more than pure evil.”

“My suggestion is termination,” Loomis says. “Death is the only solution for Michael. There’s nothing to be gained from keeping evil alive.”

Nonetheless, two more installments followed.

The violence we see perpetrated against women in the original film is outdone by screenwriter Jeff Fradley in the 2018 version of Halloween. Indeed, we see an escalation in the latest trilogy. Fradley and director David Gordon Green not only demonstrate that, 40 years on, there remains an appetite for and acceptance of misogynist cinematic celebrations of the terrorization of females, but they also fuel this appetite.

In Fradley/Green’s Halloween, we see endless violence against women. Michael Myers breaks into Laurie Strode’s home and attempts to murder her and Karen. He takes Laurie’s head, bangs it against a door, grabs her by the throat, pushes her out a second story window, throws her against a wall and hits her with a poker. He grabs Karen by the leg and pulls her down basement stairs. In another scene, Allyson is trapped in the backseat of a police car with him until she manages to escape.

Laurie, Karen, and Allyson are not Myers’ only female victims. Podcaster Dana Haines is hunted by Myers, who finds her in a gas station bathroom stall, lifting her off the floor and strangling her, breaking her neck. He bludgeons a woman to death (off-screen) with a hammer after breaking into her house (we get a shot of her head resting on a table in a pool of blood). He grabs a woman by her hair and sticks a knife through her neck. Yet another babysitter, Vicky, is shown making out with her boyfriend. When the frightened child interrupts them, she goes upstairs to comfort him, only to find Myers hiding in a closet. He drags her across the floor by her leg and stabs her to death.

By the end of the movie, Laurie, Karen, and Allyson are still alive, though little relief is offered to female viewers, as the three are left injured and bloodied, barely having escaped. Stretched out in the box of a pickup truck driving them away from Laurie’s burning house, they look tired, broken, and defeated. Moreover, it appears Myers might escape a fiery death, given that firemen are on their way to fight the blaze…

Though some feminist theorists argue this ending is a win against their “oppressor,” the victory is not a great one for the women, and the idea that female viewers might feel empowered, rather than demoralized from this orgy of violence, is laughable.

Halloween Kills’ screenwriter, Scott Teems, manages to go even further. Had Teems and director David Gordon Green set out to create a misogynist feast, it is unlikely they could have done better.

The 2021 film opens with a girl calling for help and for her mother, and ends with Michael Myers stabbing Karen to death. Viewers are shown flashbacks to Annie’s murder and Marion’s assault in the original Halloween. Myers terrorizes Sondra in her house and stabs her in the throat with a broken fluorescent tube. He hits Vanessa — dressed up in a “sexy nurse” costume for Halloween, barely covering her bottom — with a car door, knocking the gun in her hand so that she shoots herself in the face. He grabs Marion by her hair and cuts off a large handful of it with a knife before stabbing her four times — she is later found hanging from a swing set, a thick metal chain wrapped around her neck. He grabs Lindsey by the throat, slams her against her car, throws her to the ground, then hunts her as she runs and hides in a wooded area. He grabs Allyson by the neck, slams her head on a banister, pushes her to her knees and tries to kill her. He stabs another woman to death… It goes on and on… Yet Myers still escapes incarceration (and death).

The male filmmakers kill off a dizzying number of female characters, but refuse to rid us of the male serial killer who is providing so much revenue for so many, depicting misogynist male fantasies.

In a 1976 interview for Rolling Stone, Marlon Brando tells Chris Hodenfield:

“But films… it’s funny. People buy a ticket. That ticket is their transport to a fantasy which you create for them. Fantasyland, that’s all, and you make their fantasies live. Fantasies of love or hatred or whatever it is. People want their fantasies over and over. People who masturbate usually masturbate with, at the most, four or five fantasies. By and large.”

What does this say about the ongoing popularity of Halloween, and the “fantasies” that people apparently want to watch over and over again? The thrill of watching terrified women being attacked, chased, stalked, beaten, and murdered seems to provide endless entertainment for millions.

To add insult to injury, we see Laurie shift blame onto herself, lamenting, in Halloween Kills, “He [Myers] created this chaos, but I’m the one that brought it all on Haddonfield.” And again, Laurie and Allyson barely make it out alive (Laurie’s daughter Karen does not).

It is easy to see that the ending might have a chilling, disheartening effect on female viewers — similar to the previous installment. The terrorization Allyson is subjected to in Myers’ childhood home is agonizing to watch. Then, for a few minutes, the audience is led to believe that Myers will be killed off by Karen and other townspeople, but he miraculously survives their attack and kills Karen, right under the police’s nose. The safety and deliverance of two lead females is briefly dangled before us, only to be yanked away just as quickly. The message conveyed through Karen’s murder is clear: in the end, the male serial killer will prevail, despite the police, a mob, and a woman’s will to survive.

The serial killer’s fate is survival, the woman’s, death.

The title of this year’s Halloween installment, Halloween Ends, implies a potential end to the series, presumably as Myers is finally killed off. However, Jason Blum, the founder and CEO of Blumhouse Productions, one of the production companies (alongside Miramax, co-founded by convicted sex offender Harvey Weinstein and his brother, Bob) behind the latest trilogy, has said he would be thrilled to keep making Halloweeen movies.

Halloween is not Blumhouse’s only misogynist production — Ouija: Origin of Evil (2016), Split (2016), and Happy Death Day (2017), to name just a few examples, also feature the terrorizing and murder of females. According to Blumhouse’s website, it has produced over 150 movies and television series with theatrical grosses amounting to over US$4.8 billion. Given the Halloween franchise’s 13 installments, Blumhouse’s track record, and the audience’s apparent appetite, we can surely expect more movies about this particular male serial killer.

Men and women alike enjoy being frightened through film — to varying degrees and by various means, which accounts for the numerous subgenres of horror. There are many theories that aim to explain why. One is that horror films give people an adrenaline rush. The thrill provided is supposed to be more enjoyable because the audience experiences no real threat. Studies have shown that men and boys enjoy horror films more than women and girls do, find them more satisfying, and watch more of them. A 2019 review of the empirical research on psychological responses to horror films reported that “[m]en tend to prefer very graphic horror material more than do women.”

A connection between the enjoyment of pornography and horror films has been explored as well. A 1987 study found that, for males, “enjoyment of pornography was a strong predictor of the preference for graphic horror featuring the victimization of women, but not the victimization of men.” Though both men and women enjoy frights provided by horror films, it is likely female viewers will find the Halloween franchise less satisfying than male viewers, due to the misogyny, and the fact that female viewers are only exceptionally given a satisfying resolution (Myers is, for example, decapitated at the end of Halloween H20: 20 Years Later, released in 1998).

Male violence against women and girls is a big enough problem as it is without turning it into entertainment via Hollywood feature films and glorifying male serial killers in theme parks. So long as there is a profit motive attached to this kind of male fantasy, it will be fed.

Alline Cormier is a Canadian film analyst and retired court interpreter with a B.A. Translation from Université Laval. In her second career she turns the text analysis skills she acquired in university studying translation and literature to film. She makes her home in British Columbia and is currently seeking a publisher for her film guide for women. Alline tweets @ACPicks2.