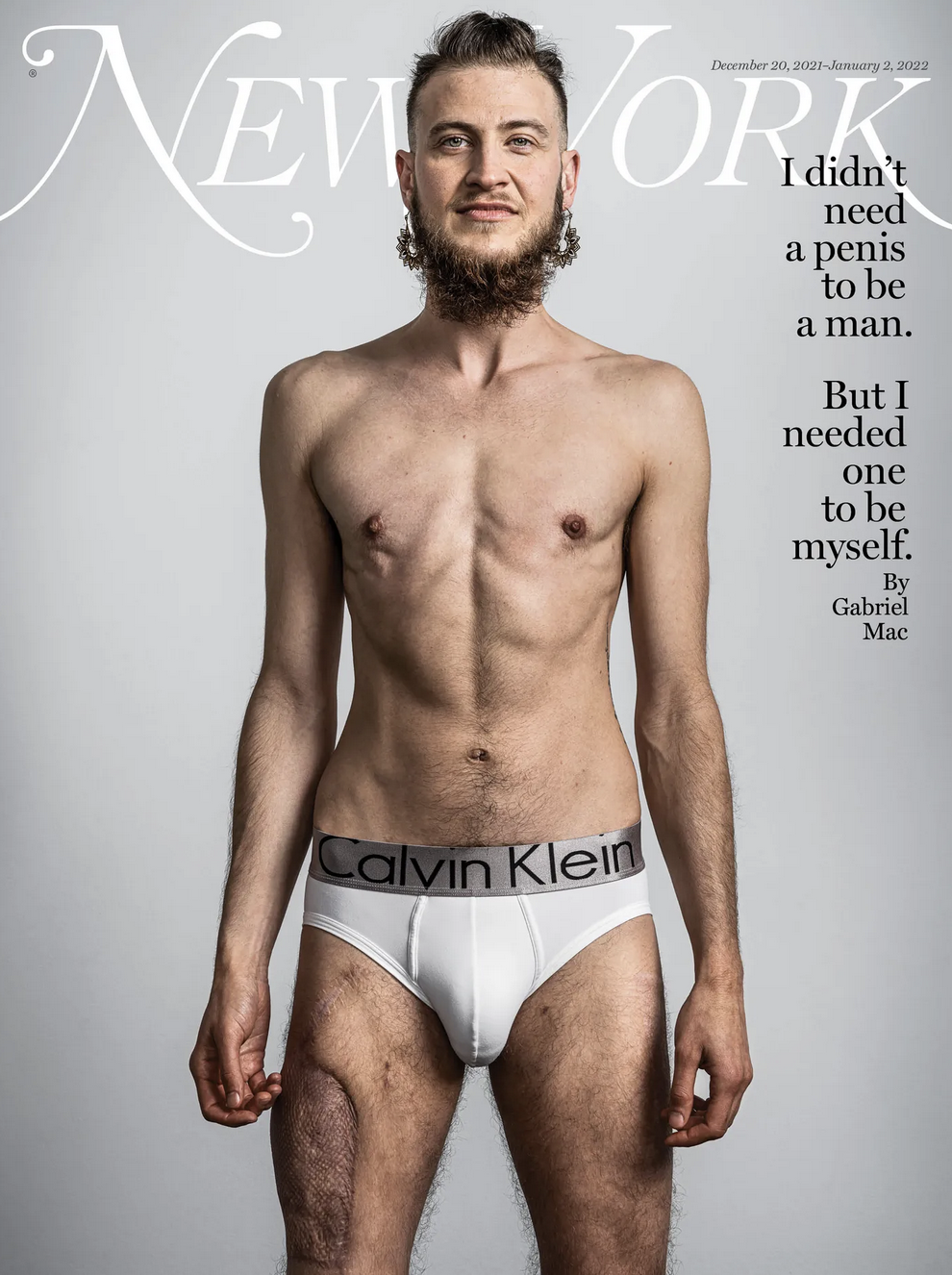

Last week, New York Magazine published an image of Mac McClelland, a female journalist now calling herself “Gabriel,” who wrote about having developed PTSD after witnessing extreme sexual violence in the aftermath of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. McClelland attempted to deal with this trauma by simulating her own rape, having an ex-lover hold her down, beat her, and force himself on her. In an article published in GOOD, she writes:

“The control I’d lost made my torso scream with anxiety; I cried out desperately as I kicked myself free. But it didn’t matter how many times I managed to knock him over to the other side of the bed. He’s got 60 pounds on me, plus the luxuries of patience and fearlessness. When I got out from under him and started to scramble away, he simply caught me by a leg or an upper arm or my hair and dragged me back. By the time he pinned me by my neck with one forearm so I was forced to use both hands to free up space between his elbow and my windpipe, I’d largely exhausted myself.”

Before this particular simulation, in 2011, McClelland told her therapist, “All I want is to have incredibly violent sex,” and later explained to ABC News that this experience of fighting off a rapist in a controlled situation, “cured her.” But this was not a first for McClelland, and it didn’t. Cure her, that is. Her partner in fake rape was a past BDSM partner and McClelland had a history of engaging in violent sex that did not end with this particular scenario. This time, he beat her nearly senseless, gathering her up into his arms afterwards to comfort her.

“I did not enjoy it in the way a person getting screwed normally would,” she writes. Rather, the goal was to survive the experience.

“As it became clear that I could endure it, I started to take deeper breaths. And my mind stayed there, stayed present even when it became painful, even when he suddenly smothered me with a pillow, not to asphyxiate me but so that he didn’t break my jaw when he drew his elbow back and slammed his fist into my face. Two, three, four times. My body felt devastated but relieved; I’d lost, but survived.”

This incident took place a long time ago, and her claim that it “cured her” might have been more believable if it weren’t so transparently backwards, but also if not for what followed.

In her 2015 memoir, “Irritable Hearst: A PTSD Love Story,” McClelland describes looking into a mirror and seeing not herself, but a boy, and of having graphic dreams where she was not the victim, but the perpetrator of violence. McClelland continued, after the scenario she wrote about for GOOD, to engage in violent sex in an attempt to deal with her trauma-related mental illness.

Eventually, it seems, she fully dissociated from her female body.

In 2019, McClelland published a story in GQ — “The End of Straight” — wherein she describes telling her therapist, “All I wanted was to saw my breast tissue off with a jagged blade and smash it into a stone table with my fists until it was particulates of pulp, dust.” After having yet another dream of herself as male, McClelland decides she is trans, and that she must remove her female body parts or die. Her femaleness was, she said, killing her.

I don’t doubt she felt this way. McClelland had only just realized that, in our culture, being fuckable — to be looked at, consumed, objectified, and sexually harassed — was a key part of being female. This can be a maddening realization. When I realized it as a young woman, I remained enraged for many years. McClelland is the same age as me, but seems to have come late to this awareness and associated anger. Her GQ essay also reveals numerous molestations and sexual assaults in her past, as well as a realization that she might be “gay.” A man who anally raped her as a girl told her, “Do you know what happens to little boys?” This, McClelland looked back on as confirmation that she was “a faggot.”

Considering all this, it’s not particularly surprising that she might want to reject her body entirely — tired of the lack of control over how she felt, had been treated, and was viewed, as a woman, and unable to rid herself of the vulnerability and trauma she connected to her “femaleness.”

Without confidence, mental stability, and a sense of control over her own psychological state and life, becoming a man might seem the perfect solution. When a trans friend asked her, “What’s your favorite thing about testosterone?” McClelland described the feeling of becoming bigger — taking up more space. The end of fragility, you could call it.

This is a woman who had been disassociating for decades to cope with what had happened to her, as a girl and a woman — who had used denial and suppression to cope (as so many do). And now, she had been offered a second solution. The first — sexual violence in a “controlled” setting — had not worked. The final step in undoing all that had been done, McClelland decided, was to get a “dick.” Then she, like in her dreams, would no longer be the victim, but the theoretic perpetrator. This was the only way, perhaps, she felt she could truly gain control.

But of course women can’t have dicks. They can have a series of experimental surgeries that strip the fat and skin from their forearms or thighs, down to the muscle, along with major nerves, arteries, and veins, and shape all this into a tube, then attempt to attach it to their pelvis, at which point they will still not have a penis, but probably a series of infections, and a need for more surgeries, as often the “penis” doesn’t take. (The description of the process itself is far more gruesome than this, and is detailed by McClelland in her piece, for those interested, if you like mutilation porn.)

McClelland, it is revealed, is not concerned with the sexual function of her “penis,” as she now identifies as asexual, an unsurprising story twist in an endless journey towards identifying out of trauma. The “penis” was really just a fantasy — part of the disassociation, the dreams, the desire to escape the sex that disempowered her.

I’m not Mac McClelland’s therapist. I can’t diagnose her with anything beyond what she’s revealed publicly. I don’t know the depths of her trauma or body dysmorphia or the variety of mental disorders she might be afflicted with. But I do know that she’s not a man, and that mutilating the body of a mentally ill woman, putting her on the cover of a magazine, telling her she is a man, and cheering her on, will not help her. What has been done to her by the media, by her therapist, and by her surgeons is reprehensible. But I suspect the only ones who will pay will be the legions of girls and women who see this as a path to love, safety, and liberation, duped into destroying themselves to comfort a few who cannot admit their mistakes, and need to sacrifice evermore vulnerable people in order to avoid the horrific reality unfolding in front of us.